Andy Jones

Condition numbers

Condition numbers measure the sensitivity of a function to changes in its inputs. We review this concept here, along with some specific examples to build intuition.

Introduction

Consider a system of linear equations represented in matrix form, $Ax = b$, where $x$ is unknown. We can easily solve this with basic tools from linear algebra.

However, how “stable” is our solution for $x$? In particular, if we were to slightly change $b$, how much would our solution for $x$ change? We can consider a slightly different problem:

\[A(x + \Delta x) = (b + \Delta b).\]We’d like to get a sense of how much this type of perturbation will affect our solution.

To begin to understand condition numbers, we should first take a detour to understand matrix norms.

Matrix norms

Similar to vector norms, norms for matrices also exist. A variety of types of matrix norms are commonly used – generically denoted as $||A||$ for a matrix $A$. We can think each of them as essentially measuring something about the “size” of the matrix.

A common way to define matrix norms is via an induced norm:

\[||A|| = \max_{||x|| = 1} ||Ax||.\]The induced norm essentially seeks a vector $x$ that is maximally “stretched” by the matrix $A$.

One example of an induced norm is the “operator norm”, which is the induced norm when we use the $L_2$ norm, $||\cdot||_2$:

\[||A||_2 = \max_{||x||_2 = 1} ||Ax||_2.\]It’s also equivalent to the maximum eigenvalue of $(A^\top A)^{1/2}$.

For a given matrix $A$, we can think of the operator norm as finding a vector $x$ that is maximally stretched when multiplied by $A$: $Ax$. Here, we measure the stretch by the $L_2$, or Euclidean, distance.

For example, if we let $A$ be the identity matrix, then $||Ax||_2 = 1$ because $A$ won’t do any stretching at all, and since we constrained $||x||_2 = 1$, we can easily see $||Ax||_2 = ||x||_2 = 1$.

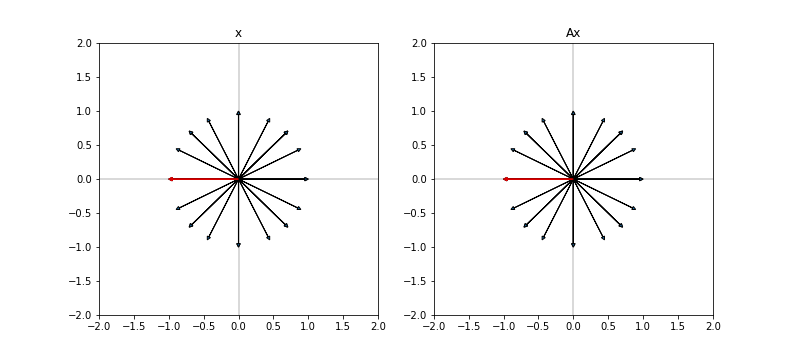

We depict this graphically below. In the left panel, we plot a subset of vectors $x$ with $||x|| = 1$. These are the vectors that we search over when we try to find the vector $x$ that has maximal induced norm $||Ax||$. In the right panel, we plot the transformed vectors $Ax$. Since $A = I$ in this case, the vectors are unchanged. Highlighted in red is the vector with maximum induced length (an arbitrary choice in this case because all vectors have the same length).

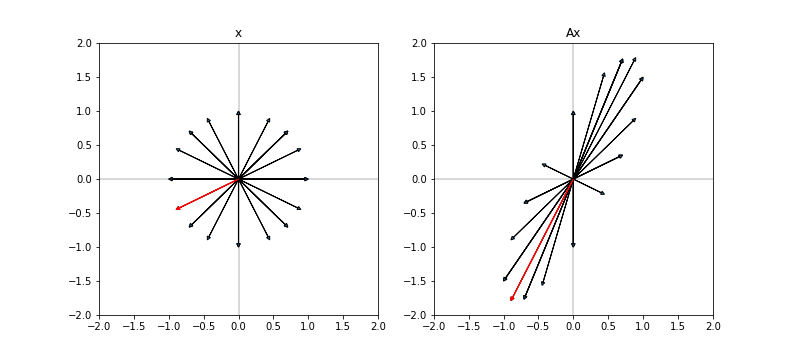

Consider a slightly more interesting case, where $A = \bigl( \begin{smallmatrix}1 & 0\ 1.5 & 1\end{smallmatrix}\bigr)$. In this case, we expect that $A$ will stretch any vector $x$. Indeed, we can see this below when we plot the original vectors $x$ and their transformed versions $Ax$:

In the left pane, the red vector is the vector $x$ such that $||Ax||_2$ is maximized ($||Ax||_2 = 2$ in this case).

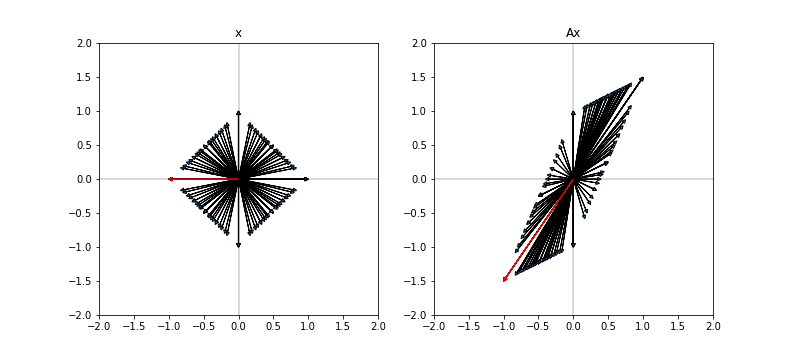

We can build similar intuition for the $L_1$ norm. In this case, the original length-1 vectors occupy a square (diamond?) about the origin. The transformed vectors $Ax$ occupy a parallelogram. The figure below shows these vectors for the matrix $A = \bigl( \begin{smallmatrix}1 & 0\ 1.5 & 1\end{smallmatrix}\bigr)$.

Now that we have some intuition about matrix norms, we can easily move on to understanding the condition number.

Condition number

In general, the condition number measures how much the output of a function changes with small perturbations to the input.

It’s easiest to first study the condition number in the context of linear transformations.

Recall from our discussion of matrix norms that matrices “stretch” vectors, and the operator norm measures the maximum possible stretch that a matrix can induce. In addition to this we can also measure the minimum stretching produced by a matrix:

\[\min_{||x|| = 1} ||Ax||.\]By measuring the maximum and minimum possible stretching, we can get a sense of the “range” of vectors produced from a matrix. This is the idea of the condition number. Specifically, the condition number of a matrix (usually denoted by $\kappa$) is the ratio of its maximum stretch to its minimum stretch:

\[\kappa(A) = \frac{\max_{||x|| = 1} ||Ax||}{\min_{||x|| = 1} ||Ax||}.\]Furthermore, if we let $Ax = y$, notice that

\begin{align} \min_{||x|| = 1} ||Ax|| &= \min \frac{||Ax||}{||x||} \\ &= \min \frac{||y||}{||A^{-1}y||} \\ &= 1 / \max \frac{||A^{-1}y||}{||y||} \\ &= 1 / ||A^{-1}||. \\ \end{align}

Thus, the condition number can be rewritten as

\[\kappa(A) = ||A|| ||A^{-1}||\]which is simply the product of two operator norms – one on $A$ and another on its inverse.

If $A$ is singular then $A$ can map any vector to another vector of length $0$, and so $\min \frac{||Ax||}{||x||}$ and $\kappa(A) = \infty$. For matrices, an interpretation of the condition number is a measure of close the matrix is to being singular (higher condition number means closer to being singular).

Condition number in linear systems

Consider the linear system $Ax = b$. Returning to the question, we started with, we can use the condition number to understand how a small change in $b$ affects $x$. In particular,

\[A(x + \Delta x) = b + \Delta b.\]Since it’s a linear system, we know that $A(\Delta x) = \Delta b$, and $||Ax|| = ||b||$. Furthermore,

\begin{align} ||b|| &= ||Ax|| \\ &\leq \max_x ||Ax|| \\ &= ||A|| ||x||. \\ \end{align}

Also, if we let $m = \min_{x} ||A (x)||$, we have

\begin{align} ||\Delta b|| &= ||A (\Delta x)|| \\ &\geq \min_{\Delta x} ||A (\Delta x)|| \\ &= m ||\Delta x||. \\ \end{align}

Putting these together, we can get a bound on the condition number of $A$. Since $||A|| \geq \frac{||x||}{||b||}$ and $m \leq \frac{||\Delta b||}{||\Delta x||}$, we have

\[\kappa(A) = \frac{||A||}{m} \geq \frac{\frac{||x||}{||b||}}{\frac{||\Delta b||}{||\Delta x||}}\]which implies

\[\frac{||\Delta x||}{||x||} \leq \kappa(A) \frac{||\Delta b||}{||b||}.\]The left-hand side, $\frac{||\Delta x||}{||x||}$ is the (normalized, dimensionless) change in the solution of the system, and the right-hand side is the condition number multiplied by $\frac{||\Delta b||}{||b||}$, which is the (normalized, dimensionless) change in the output. This gives us an upper bound on the change of the solution when the output is perturbed. Importantly, this bound is completely determined by the condition number.

Arbitray functions

The condition number applies much more broadly than just in linear systems. For an arbitrary function $f(x)$, the condition number is

\[\kappa(f) = \lim_{\epsilon \to 0} \sup_{||\Delta x|| \leq \epsilon ||x||} \frac{||f(x + \Delta x) - f(x)||}{\epsilon ||f(x)||}.\]References

- Wikipedia page on condition numbers

- Cleve Moler’s blog post on condition numbers.

- Fan, J., Li, R., Zhang, C.-H., and Zou, H. (2020). Statistical Foundations of Data Science. CRC Press, forthcoming.

- Prof. Nick Higham’s blog post.