Andy Jones

$\chi$ triangles

Describing $\chi$ random variables as the lengths of vectors.

$\chi^2$ random variables

Let $X_1, X_2 \sim \mathcal{N}(0, 1)$ and define $Y = X_1^2 + X_2^2$.

From the definition of a chi-square random variable, we know that $Y$ follows a chi-squared distribution with two degrees of freedom,

\[Y \sim \chi^2_2.\]$\chi$ random variables

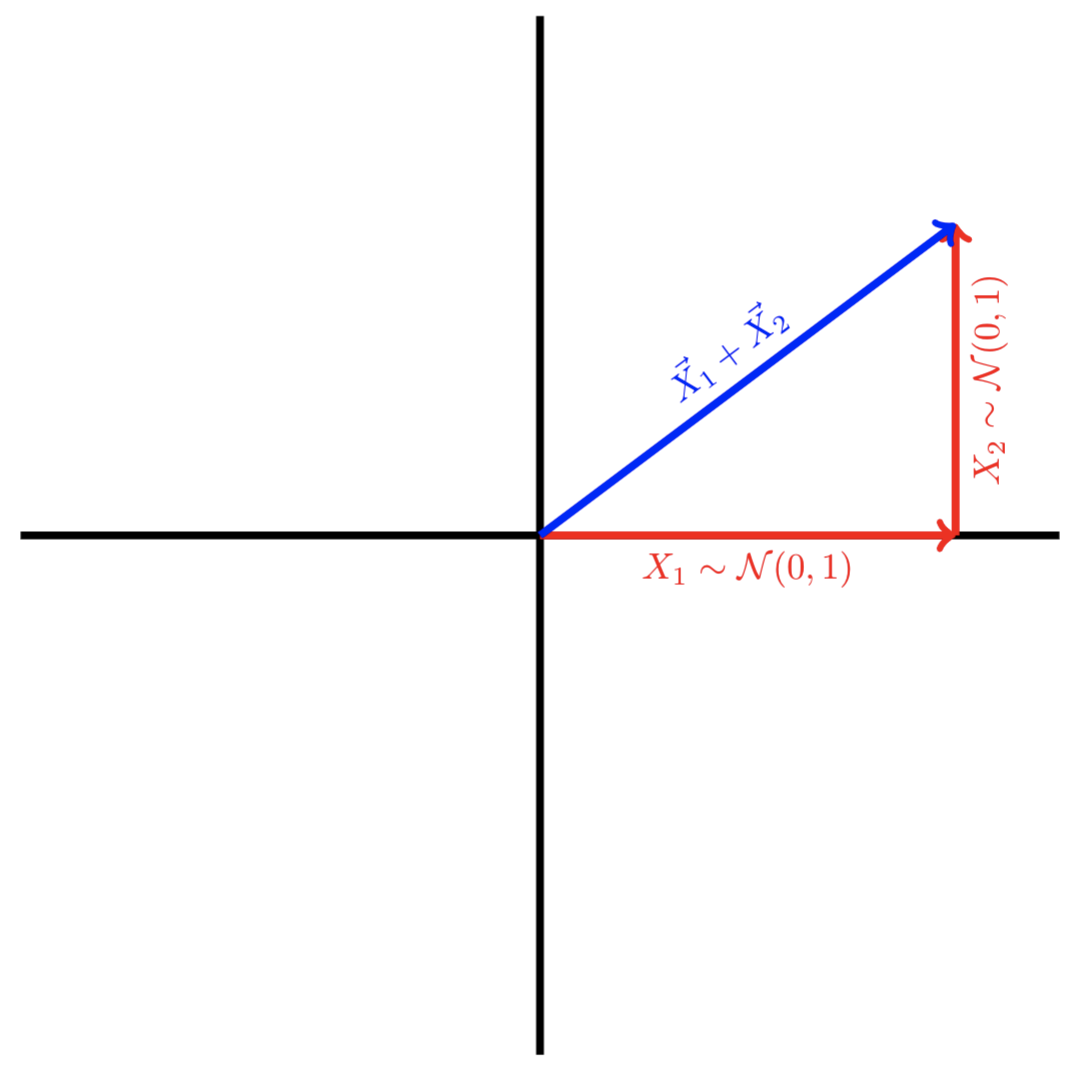

Now, let’s plot $X_1 + X_2$ in vector form. As a slight abuse of notation, let $\vec{X_1} = \begin{bmatrix} X_1 \\ 0 \end{bmatrix}$ and $\vec{X_2} = \begin{bmatrix} 0 \\ X_2 \end{bmatrix}$.

By the Pythagorean Theorem, the length of $\vec{X_1} + \vec{X_2}$ will be $\sqrt{X_1^2 + X_2^2}$. Equivalently, the length is $\sqrt{Y}$.

This means that the length of a random vector constructed from the sum of two standard normals follows the distribution of the square root of a $\chi^2_2$ random variable. This is also known as a chi-distributed random variable with two degrees of freedom. Let $X = \begin{bmatrix} X_1 \\ X_2 \end{bmatrix}$. Then,

\[||X||_2 \sim \chi_2.\]More generally, we can think about the sum of $d$ squared stanadard normals. In particular, if

\[X \sim \mathcal{N}(0, I_d),\]then

\[||X||_2 \sim \chi_d.\]This has the same geometric interpretation but for higher-dimensional “triangles” (simplices with an orthogonal corner): the length of the hypotenuse follows a $\chi_d$ distribution.