Andy Jones

The tunnel model of research

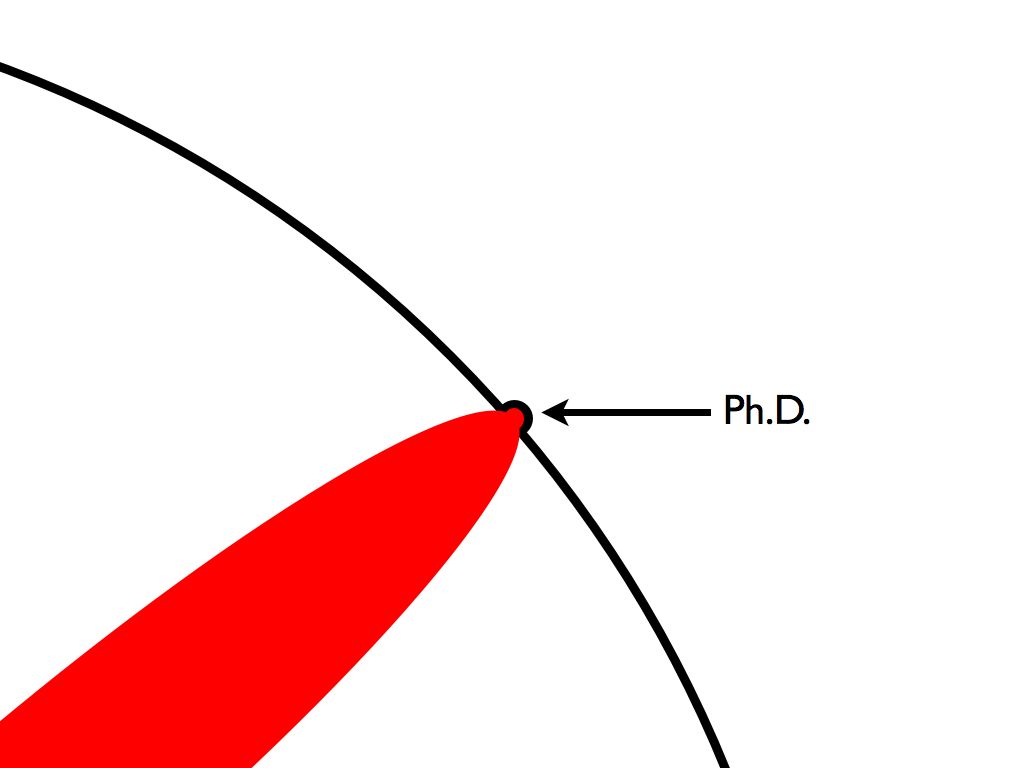

One of my favorite visual models of what it means to do a PhD comes from Matt Might. His diagram (reposted below) shows that PhD research pushes the boundary of human knowledge further out just a tiny bit. In his, a circle represents the totality of scientific knowledge, and a PhD’s worth of research pushes one part of the edge of this circle outward.

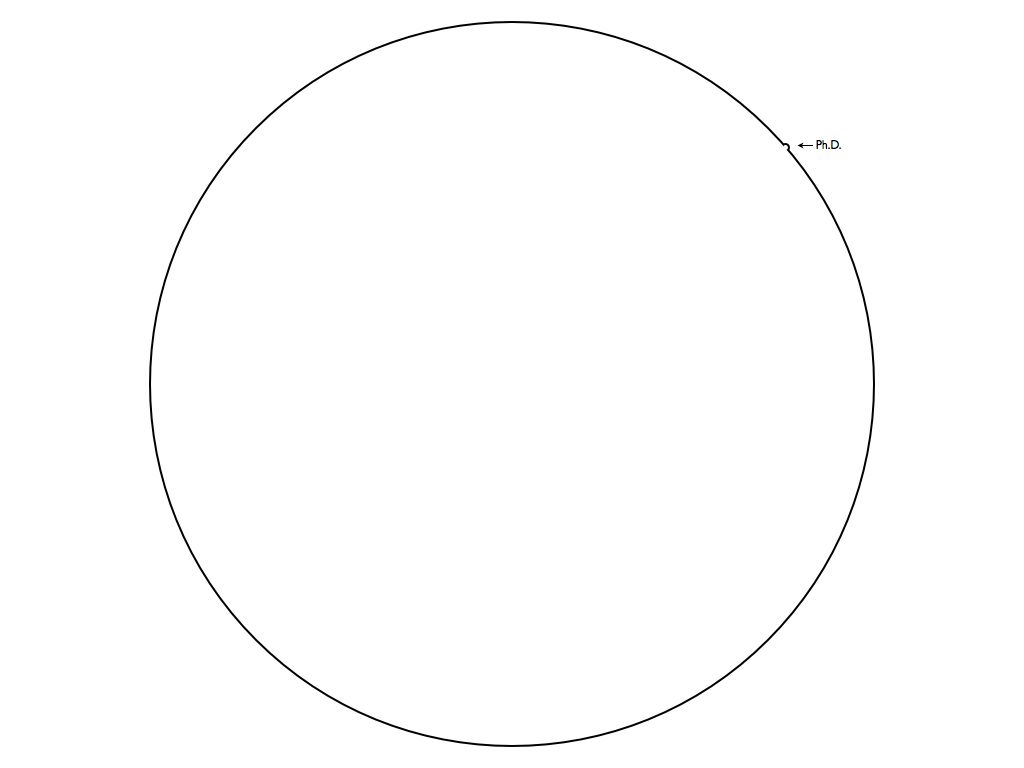

When this bump in the boundary is viewed in the context of the humans’ entire knowledge base (the entire circle), we see that it’s effectively negligible. Might’s next diagram below shows this visually.

While this diagram is a fairly accurate (and humbling) depiction of one researcher’s contribution to knowledge, it errs on a crucial point. Depicting the totality of scientific knowledge as a circle implies that this body of knowledge is well-connected and dense within this convex boundary. However, in reality our body of knowledge is highly fragmented and disconnected. At the frontier of research, each scientific discipline studies extremely narrow topics, making it difficult to effortlessly travel from one point in the circle to another (i.e., from one field of study to another).

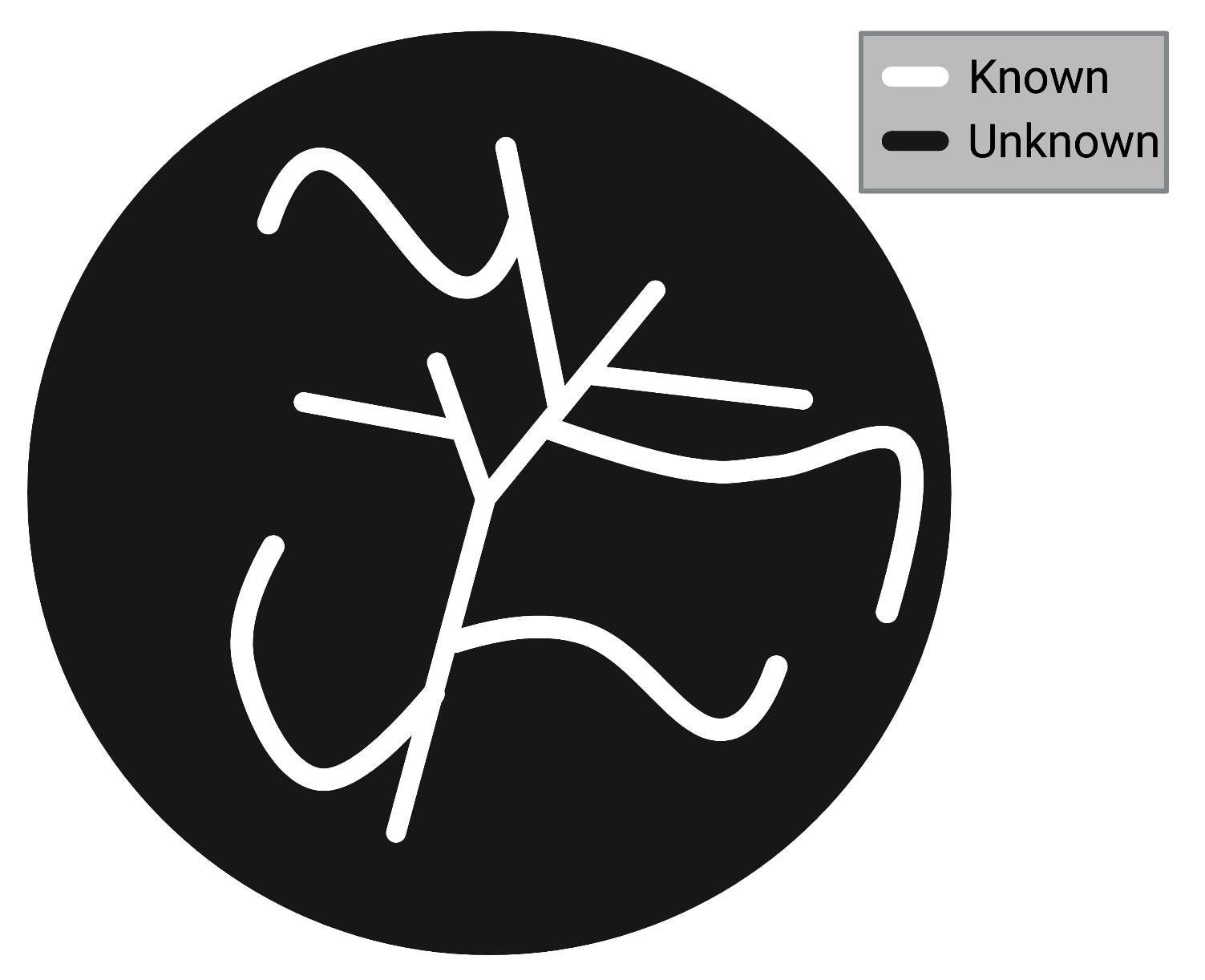

I believe a better way to depict scientific knowledge is as a map of underground tunnels. In this model, each tunnel represents a scientific (sub-sub-sub-)sub-domain, and as research progress is made, the tunnel gets longer. At the end of each tunnel is a team of scientists (academic or otherwise) chipping away at the walls, trying to find what’s behind them.

Under this model of research as a series of tunnels, the universe of knowledge is mostly dark (unknown), with the light-filled tunnels occupying a minority of the space. My proposed edit to Matt Might’s visual model is below, where the “known” areas are connected (yet narrow) within a larger “unknown” area.

Features of the tunnel model

Like any model of the world, the tunnel model is most definitely wrong in some ways, but the hope is that it’s also useful and elucidating in other ways. One way we can check how well the tunnel model describes reality by seeing if it explains and predicts real-world phenomena. Let’s consider some of the implications of the model, and compare these implications with how research works empirically.

Forks

As a start the tunnel model captures the fragmentation that happens in research; in particular, it captures events where a research field splits into multiple sub-fields. We can call these forks.

Forks happen all the time, often spurred by one subset of researchers preferring to think about a specific field in a certain way, while another subset sticks with the old way. Examples include the split of machine learning into a “deep learning” sub-community and a “non-deep learning” sub-community; the split of statistics into Bayesian and frequentist communities; and the split of neuroscience systems-level studies and neuron-level studies.

In most cases the number of forks is huge (each branch of a fork can then spawn other bifurcations in the future), so the tunnel model has a fractal-like property of having nearly infinite splits.

Convergence points

To the contrary, the tunnel model also allows for convergence points, where two fields arrive at the same idea or conclusion via different routes.

One specific example of this is the development of principal component analysis (PCA), which is a statistical tool for dimensionality reduction. PCA has been discovered and rediscovered by statisticians, probabilistic modelers, deep learning enthusiasts, and game theorists. All of these groups framed the problem in a unique way, but they ultimately arrived at the same idea.

Fragmentation and close misses

Importantly, the tunnel model implies that the body of scientific knowledge is fragmented, and that there remain lots of open questions even in areas directly adjacent to well-studied fields. Also, there may be many “so-close-yet-so-far” when a researcher or research community decides to pursue one avenue of research when a more fruitful avenue was right next door. In the model, this corresponds to a tunnel just barely missing a success when it could have turned and easily obtained it.

Cross-disciplinary research

Finally, the tunnel model implies that it’s difficult and laborious to draw connections between research fields. Consider a researcher who specializes in field A and is trying to make connections between her work in field A and another field, which we’ll call field B. The scientist currently sits at the end of tunnel A. In order to make connections between A and B, she would either have to start chipping away in the general direction of tunnel B, or walk back to the base where tunnels A and B meet and start chipping away at the corner between A and B. These two approaches map onto two cross-disciplinary research styles that are observed in practice:

- Building connections between A and B from first principles, which takes more time and could even be futile in the end (equivalent to walking back to convergence point of A and B).

- Haphazardly applying state-of-the-art knowledge or techniques from field A to the frontier of field B without drawing on more fundamental or older knowledge from the fields (equivalent to trying to brute-force a new tunnel from endpoint of A to endpoint of B).

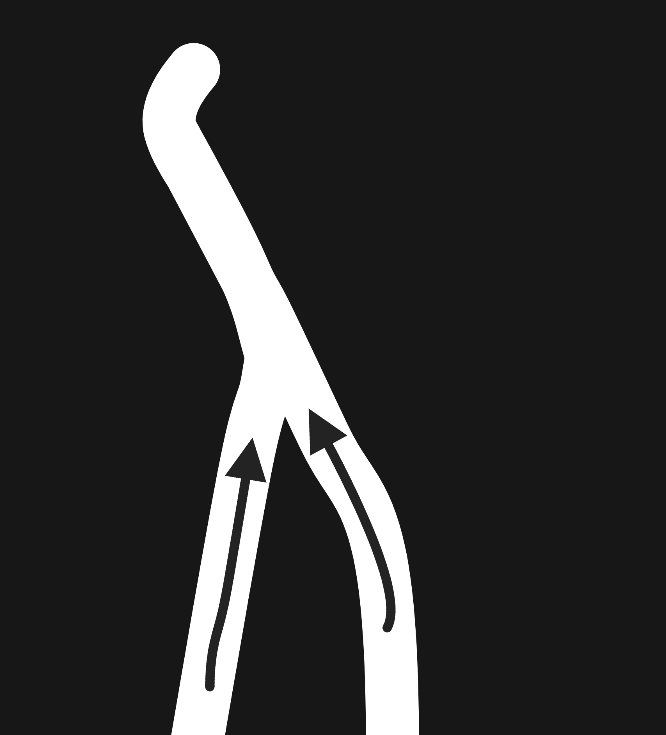

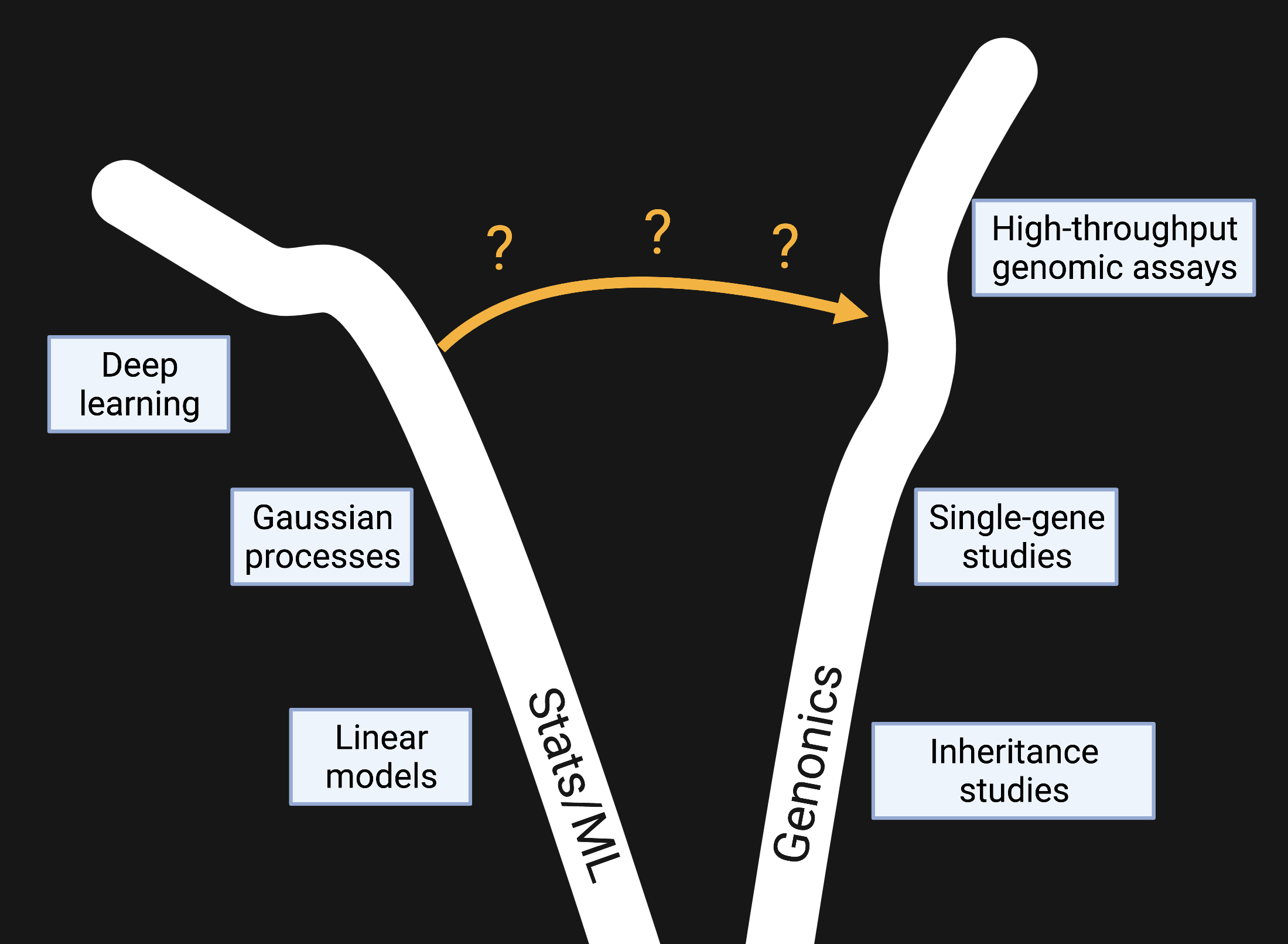

Consider an example: the application of statistical and machine learning (ML) tools to the study of genetics and genomics. The diagram below depicts this scenario.

The “stats/ML” tunnel on the left shows the progression from linear models to more complex tools like Gaussian processes and deep neural networks. (Of course, this is an extreme simplification meant for demonstration purposes.) The “genomics” tunnel on the right shows the progression from basic inheritance studies used by scientists like Gregor Mendel to more modern technologies that allow for broad sequencing of genomes.

It may be tempting to directly apply complex ML tools, such as state-of-the-art deep neural networks, to the latest high-throughput genomic data. And in many cases, there may be useful downstream insights from doing so. However, given the complexity of each field at the end of its tunnel, it’s difficult to fully understand the assumptions and consequences of such an application. Deep neural networks are still poorly understood theoretically, and genomic assays are still noisy and imperfect representations of reality. Thus, a perfect union of the two remains extremely difficult given the sharp divergence between the fields.

Conclusion

While it’s certainly an imperfect model of research endeavors, the tunnel model elucidates some important aspects of the research process across multiple time scales.

References

- Matt Might, a professor in Computer Science at the University of Utah, created The Illustrated Guide to a Ph.D. to explain what a Ph.D. is to new and aspiring graduate students. (Matt has licensed the guide for sharing with special terms under the Creative Commons license.)