Andy Jones

The value of reading old research papers

\(\DeclareMathOperator*{\argmin}{arg\,min}\) \(\DeclareMathOperator*{\argmax}{arg\,max}\)

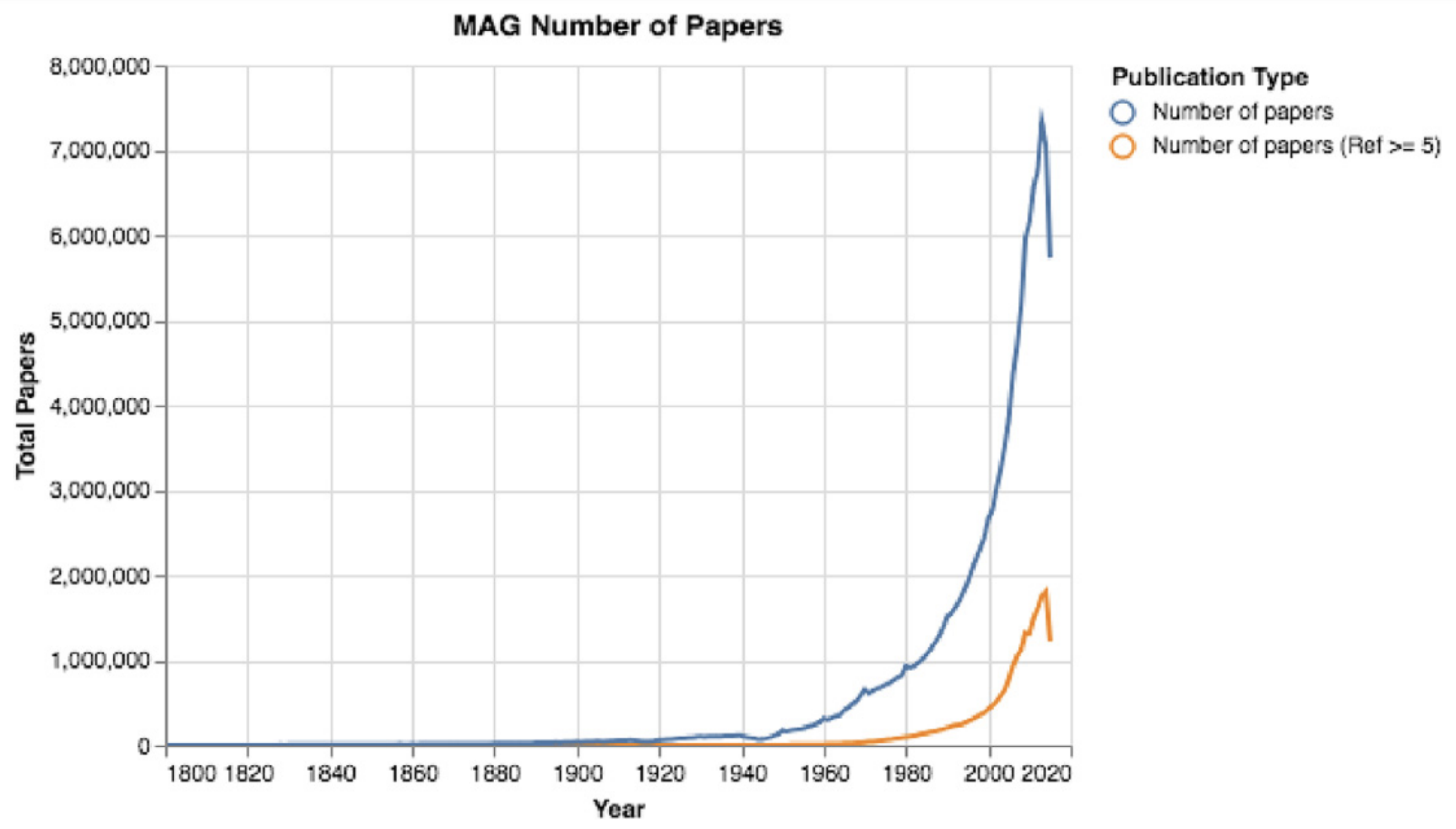

The number of research papers has exploded in the past couple decades. Consider the plot below showing the number of papers published each year from 1800 to the present (from this paper by Fire and Guestrin).

This growth has been further accelerated by preprint servers, like arXiv and bioRxiv, where researchers can deposit their (non-peer-reviewed) manuscripts with very little effort.

As this growth occurs, research communities tend to become more and more specialized over time, with lots of sub-communities occupying small niches. This hyper-specialized ecosystem leads to research papers containing more jargon, and these papers become less accessible to a lay person trying to understand them. Comprehending these papers poses a high barrier to entry, requiring readers to have lots of prior knowledge in the field to make sense of their findings.

Old papers

For many fields, it can be enlightening to read older papers (say, >20-30 years old) in addition to the most recent, state-of-the-art papers. After all, these older papers are the ones that laid a foundation for today’s jargon-filled papers.

The main benefits of reading older papers are:

- Older papers often present a clearer problem statement and provide more intuitive motivation for the work.

- Older papers teach a lesson about the history, sociology, and nonlinearity of science.

Present-day niche research papers are often motivated by previous research (e.g., “We build off of the work by Doe et al.”). On the other hand, older research papers tend to be motivated by a more fundamental problem (“We present a solution to problem XYZ”). In trying to understand the motivation and long-term goals of a line of research, it is useful to strip away all comparisons to related work. Instead, it’s instructive – especially for people new to the field – to build the motivation from first principles. Older research papers typically provide a more direct path to this.

On a more historical level, reading older research papers teaches a lesson about the evolution of ideas and research fields. The writing style of academic papers is typically very confident and exact, and it may seem to the reader that the authors carried out the research effortlessly. However, scientific progress is usually nonlinear, having lots of dead ends and red herrings. While this may not be evident from any individual paper, studying a string of papers from the same field that span decades makes this clear. For example, you might discover one paper from 1970 that presents a groundbreaking result, only to find another paper from 1980 that completely debunks that result. Studying the history of a small cross section of science can help a researcher maintain a healthy level of skepticism and appreciate these unexpected turns.

A case study: Experimental design

Let’s consider a case study tracing the evolution of a line of work through time. Here, we’ll look at the field of experimental design, which refers to a body of statistical methods that attempt to find the best ways to conduct experiments (e.g., biological, agricultural, or geological studies).

The beginning of this work can be traced back to at least 1926, when Ronald Fisher became interested in studying the optimal way to divide up a plot of land to run agricultural experiments. Consider the simplicity of the title of one of his first papers on the topic: “The arrangement of field experiments.” The title is concise and to-the-point. In the paper, Fisher considers a very specific example, and refrains from the usage of highly technical language. For example, one passage reads:

For the purpose of variety trials, and of those simple types of manurial trial in which every possible comparison is of equal importance, the problem of designing economical and effective field experiments, reduces to two main principles (i) the division of the experimental area into the plots as small as possible subject to the type of farm machinery used, and to adequate precautions against edge effect; (ii) the use of arrangements which eliminate a maximum fraction of the soil heterogeneity, and yet provide a valid estimate of the residual errors.

He’s considering a very specific application: a “manurial trial,” which studies the difference in growth for crops treated with and without manure.

Let’s jump forward a couple decades to 1951, by which time the field experimental design had become more formalized. In a paper from that year, George Box proposed a way to optimize the design of chemistry experiments. Near the beginning of the paper, he states the problem as follows.

In the whole $k$ dimensional factor space, there is a region $R$, bounded by practical limitation to change in the factors, which we call the experimental region. The problem is to find, in the smallest number of experiments, the point ($x_1^0, \dots, x_t^0, \dots, x_k^0$) within $R$ at which $\eta$ is a maximum or a minimum.

We can immediately see that the problem formulation has become more technical, mathematical, and dense compared to Fisher’s description. Of course, here I have taken an excerpt out of the context of the paper, making the mathematical notation confusing when read in isolation, but we can already see that the reader will need to make several steps to understand how the mathematical formulation maps onto reality. On the other hand, we can appreciate the innovation that Box pursued by precisely characterizing experimental design as a mathematical problem. Fisher’s description, on the other hand, was largely qualitative and lacked mathematical formalism.

Finally, let’s jump ahead to 2009 to look at a paper written by Srinivas et al. This paper, titled “Gaussian Process Optimization in the Bandit Setting: No Regret and Experimental Design” has been very impactful (for good reason) in the fields of sequential decision making and experimental design. It proposes a flexible framework for making decisions when very little prior information is known.

Consider the first two sentences of the abstract:

Many applications require optimizing an unknown, noisy function that is expensive to evaluate. We formalize this task as a multi-armed bandit problem, where the payoff function is either sampled from a Gaussian process (GP) or has low RKHS norm.

Already, we can observe the highly technical nature of this work. Terms such as “multi-armed bandit,” “Gaussian process,” and “RKHS norm” would probably have been foreign to Fisher, but have now become central to the motivation for the work. Of course, there are several good reasons for this, and having to re-explain the problem statement from first principles would be tedious and might distract from the paper’s contribution. Nevertheless, for a person who may be new to the field of experimental design, it shows the value in understanding the fundamental problem first – a task that reading older papers can help with.

Conclusion

In general, there are substantial benefits to reading older research papers. They are particularly instructive for people who are new to a field.

The argument presented here shouldn’t be confused with a stance that more recent research papers are inherently bad, or that the community’s progress toward becoming more specific and technical is bad. In fact, I view these trends as indicative of meaningful progress in most cases. Instead, I would argue that it’s worth viewing a research field as a tree, with lots of branch splits when new ideas are developed and refined. While the branches farthest out might be the most recent and hottest ideas, it’s worthwhile coming back to the roots from time to time to understand that new branch’s origin.

References

- Fisher, R. (1926). The arrangement of field experiments.

- Box, George EP, and Kenneth B. Wilson. “On the experimental attainment of optimum conditions.” Breakthroughs in statistics. Springer, New York, NY, 1992. 270-310.

- Srinivas, Niranjan, et al. “Gaussian process optimization in the bandit setting: No regret and experimental design.” arXiv preprint arXiv:0912.3995 (2009).